Amidst the brouhaha around the Delhi gang-rape case, concerns are raised whether legislation alone will ensure the safety and rights of domestic workers across the country

By Saher Baloch, New Delhi

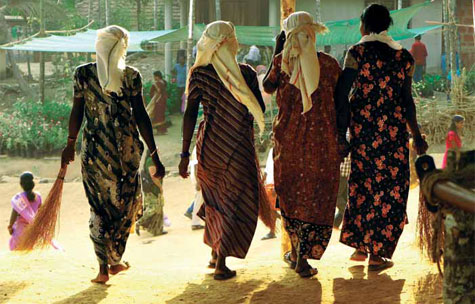

Sitting amidst friends and colleagues early on a Sunday morning, Phulkeriya Minz is busy making arrangements for the day. A domestic workersʼ meeting is expected to start any minute now.

Chota Nagpur Working Women Association (CNWWA), located in West Kidwayi Nagar, has been a placement agency for domestic workers in Delhi since 1982. This weekly meeting is a chance for the domestic workers to talk. Mostly, they talk about the problems they face and the treatment meted out to them by their employers.

“Think of it as a way of venting,” explains Minz. Most of these workers hail from Jharkhand. This is the only place where workers are allowed to fearlessly speak their mind.

Their conversations and complaints get documented,

she adds.

With the death of the victim of the Delhi gang rape

incident recently, the debate at the association has shifted

more towards ensuring the physical safety of domestic

workers. Even though a recent inclusion of domestic workers

in a long awaited Sexual Harassment Bill was lauded in August

2012, many workers at CNWWA think it has nothing to do with

them.

“Who cares for us exactly?” asked a middle aged woman, introducing herself as Shanti, (last name not given).

“What can a piece of paper guarantee? I know for a fact that I

have to take care of myself; no law can do that for me.”

Shantiʼs opinion is shared by most of her colleagues, who nod

in agreement. They mention a host of other abuses that are

not reported at all.

Just last week Minz went to Gurgaon to meet an employer of one of the women from CNWWA. The complaint was that the woman was asked to sleep under a staircase with even a blanket or a pillow. In another case, a worker reported that she was beaten by her employer in Ghaziabad after she used the common bathroom in the apartment. “You donʼt need a law to make people behave or to feel for the other (sic),” adds Minz angrily, while the chatter in the room fizzles out.

It is to avoid such incidents that CNWWA pre-arranges the terms and conditions of employment before placing a domestic worker.

Minz negotiates every detail, right

from salary to the domestic workerʼs

meals and sleeping arrangements. This

is done in the presence of both

employer and employee. For instance,

the initial salary is fixed at Rs. 6,000 a

month and above. There is a clause

specifying working hours, which is not

supposed to be more than 8, and an

added section about bedding. In

another clause the employers are asked

to give the employee a two hour

break every day. Most of these

clauses are accepted by the employers,

Minz added.

However fiery and forthright these

women are in their

speech, they do not say

much when it comes to

sharing instances of

sexual harassment at

the workplace. Recently,

a 13-year-old girl was

rescued from an

apartment in Dwarka

after her employers had

locked her in and gone on holiday. This

is just one of the many cases that

expose the vulnerability of the domestic

workers to abuse and exploitation.

When asked whether or not

workers report sexual or physical

abuse, Minz was quick to clarify, “Look,

so far we havenʼt come across such

incidents at all. Thatʼs the only reason

we donʼt place younger women, only

mature ones.”

This decision came after a recent

incident, where one of the young

workers in Kidwayi Nagar quietly left her

employment without citing the exact

reason. One of her friends later reported

that the girl was molested by her

employerʼs husband. Though placement

agencies insist they are in constant

touch with the women they contract out

for employment, it remains unclear

whether they can ensure their safety

from within the confines of an

employerʼs home.

Jaya Iyer, a social activist,

believes that no amount of legislation

can bring security. However a legal

framework is needed and is

important. “Legislation is not enough. Mindsets and cultures have to be

changed and the perception of privacy

or ʻghar ki baatʼ must be breached. Itʼs

high time,” she says.

At the same time, she adds that efficacy of the law is impossible until a domestic worker reports abuse or poor treatment.

Big exodus to urban areas

With an estimated number of half a

million domestic workers, Delhi has

seen many phases of external and

internal exodus. In the 70ʼs, men from

Nepal would come in hordes to the city

looking for menial jobs, mostly as

guards and servants. The 80ʼs saw an

influx from West Bengal, Orissa and

Chattisgarh.

“From the 90ʼs and onwards, there has been an internal migration going on,” adds Iyer. Most workers were flocking in from Central India.

For the past one decade though, with natural disasters like the tsunami in 2004, and an overall unrest in some tribal areas, the city has seen an influx of migrants from Jharkhand and other connected areas.

With no knowledge of language

and the life in cities, many women come

to Delhi either to look for better

employment to support their families or

to support their own education. But

somewhere in the middle they fall into

the trap of people on the look out to earn

a quick buck.

Minzʼs CNWWA is among the 2300 placement agencies in the city out of which only 269 are properly registered. Most of these agencies are on a tricky platform to redress abuses, thus demonstrating a need for a national policy or guideline for the rights of workers.

With the ongoing debate on

domestic workers rights, activists like

Iyer feel that it might take another

decade to properly see the recently

amended Sexual Harassment Bill

through. The bill initially excluded

domestic workers but after protests

from civil rights activists, the

domestic workersʼ rights were included

in mid-2012.

• An earlier version of the draft left out domestic workers provision in 2010.

• In 2012, it was unanimously passed in the parliament.

• Fine of upto `50,000 will be charged in case of noncompliance of the law.

• Unlike legislation in many other countries the bill does not provide protection to men.

Citing an example, she said that,

the Domestic Violence Act was passed

in 2005 after being ʻdiscussedʼ for eight

to 10 years. “The fact of the matter,”

she adds, “is that the administration

hasnʼt got its act together, even as

abuse of workers increases. At the

same time the laws canʼt work without

the social support of people,” citing the

example of the recent Delhi gang rape

incident, in which people from all walks

of life took to the streets in support of

the victim.

In the meantime,

there are a lot of abuses

taking place that go

unnoticed. Out of these

cases only a select few

come out in the open,

depending on the extent

of barbarity.

“It is more about social interven tion at every level. It needs to be about empowering workerʼs groups, validating intervention and for people like us to be more sensitive to such incidents,” Jaya adds.